On the basis of his experiments on stabilised retinal images Yarbus concluded: “For optimal working conditions of the human visual system, some degree of constant (interrupted or uninterrupted) movement of the retinal image is essential. If a test field (of any size, color, and luminance) becomes and remains strictly constant and stationary relative to the retina, it will become and remain an empty field within 1-3 sec”. It is this aspect that reviewers of the book focussed upon.

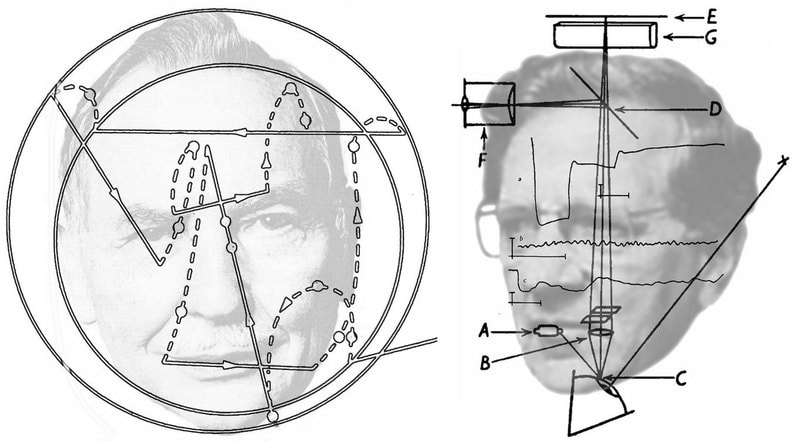

From the early 1950s optical techniques were employed to measure very small eye movements during fixation and also to present stimuli that were optically stabilised on the retina; that is, the stimuli moved with movements of the eyes. Three research centres were very active in this initial phase, Ditchburn and Ginsborg at Reading University, Riggs and Ratliff at Brown University, and Barlow at Cambridge. Together they showed that during fixation the eyes undergo high frequency, low amplitude tremors onto which are superimposed slow drifts and rapid flicks or microsaccades. These were demonstrated by sets of complex compensatory optical systems or with contact lens devises. The pattern of involuntary eye movements can be seen in figure below left superimposed on the portrait of Floyd Ratliff, one of the pioneers who used such devises. In 1950 Ratliff and Riggs employed an optical lever system and photography to record the involuntary motions of the eye during fixation. They found small rapid motions of about 17.5 seconds of arc at 30-70 Hz, slow motions of irregular frequency and extent, slow drifts and rapid jerks. Two years later Barlow placed a droplet of mercury on the cornea and photographed the eye during motion and fixation (figure below right); the instabilities during fixation were small but measurable. He confirmed his photographic measurements by comparing them with afterimages.

Left, Unsteady gaze by Nicholas Wade. Floyd Ratliff within a pattern of involuntary eye movements during fixation; the high-frequency tremor (not shown) is superimposed on the slow drifts (dashed lines), with intermittent microsaccades. Right, Mercurial movements by Nicholas Wade. Horace Barlow with the optical system he employed to record reflections from a droplet of mercury on the cornea and the records of eye movements during fixation showing: a, “continuous drifts”; b, “rapid vibration”; and c, “slow irregular wobble”.

Even from the first experiments with stabilised retinal images, it became clear that the curious phenomena observed under such conditions have direct relation to some general principles of visual information processing. At those times, neurophysiologists and psychologists were very much influenced by information theory. One of the basic claims of this theory is that “a constant signal doesn’t contain any information”. And in agreement with this claim visual neurophysiologists found that many visual neurons were silent when the eyes were exposed to constant illumination (even when very bright). Accordingly, it was concluded that image fading meant eliminating constant signals as the unnecessary ones. In fact, such arguments do apply to information transmission over great distances but not for the image analysis and interpretation.

Later investigations presented evidence that Yarbus’s concept, implying inevitable and irreversible fading of a visible image evoked by stabilised retinal stimulus of any size, colour, and luminance in 1-3 seconds after its onset, was not valid in a general case. It has been demonstrated that, even with Yarbus’s stabilisation techniques, the lifetime of visible images varies from fractions of a second to the whole stimulus duration – up to many minutes, depending on many factors: monocular or binocular viewing, level of ambient illumination, stimulus size, brightness/lightness, contrast, colour, etc. (The analysis of the literature related to this issue is given in Rozhkova & Nikolaev, 2015.)

It has now become evident that a number of mechanisms functioning at several levels of visual information processing contribute to the phenomenology of stabilised image perception: active deleting of false images, subtraction of successive frames to eliminate additive noise, local and global adaptation, binocular rivalry, suppression of improbable hypotheses at the cognitive level, etc. Retrospectively, it became clear that Yarbus based his fundamental statements on the data obtained in specific conditions and treated these statements as universal laws. However, due to his inventiveness, clear formulation of the ideas, and persistence in defending his position, Yarbus greatly promoted investigations aimed at revealing the general principles of visual information processing.